The principles:

“The natural formation of the country is the soldier’s best ally; make use of it to your advantage.”

“When the general is weak and without authority; when his orders are not clear and distinct; when there are no fixed duties assigned to officers and men, and the ranks are formed in a slovenly haphazard manner, the result is utter disorganization.”

“The general who advances without coveting fame and retreats without fearing disgrace, whose only thought is to protect his country and do good service for his sovereign, is the jewel of the kingdom.” — Sun Tzu

Ground First

Sun Tzu makes a simple demand: know the ground on which you stand.

The proper ground turns disadvantage into leverage. The wrong ground turns strength into exposure. Terrain is not merely soil; it is topology, logistics, law, culture, and architecture. In the modern world, it includes cloud regions, compliance borders, identity planes, and network topology. Choose well, and the fight often narrows into something you can actually win.

This is not an abstract chapter. It’s a practical one.

If you’ve ever seen a breach unfold, you’ve witnessed terrain deciding outcomes in real time: attackers rarely “win” because they are stronger; they win because they enter through easy ground, move through poorly observed corridors, and reach valuable systems before defenders can orient.

The defender’s job is to resist. It is to shape the ground, so the adversary’s best options become expensive, loud, or impossible.

Types of Terrain – What They Feel Like, What They Demand

Sun Tzu names a wide variety of ground. In practice, the terrain we face, militarily, digitally, and politically, collapses into recurring patterns: open, narrow, steep, encircled, and expansive.

Each demands a distinct strategy. Each punishes a different kind of arrogance.

Open Ground – Fast, visible, unforgiving

Open ground is where you can be seen.

In war, it is flat land with no cover: movement is easy, concealment is costly, and discipline decides whether speed becomes an advantage or panic. Detection and clean maneuvering are important because contact is constant.

In cybersecurity, open ground is your public-facing surface area: internet-exposed services, public APIs, external portals, and remote access entry points. This is not where you want complexity. You want ruthless simplicity, fewer doors, fewer endpoints, fewer exceptions, paired with strong telemetry. Frameworks like the CIS Controls and NIST CSF explicitly prioritize inventorying and minimizing public-facing assets—making clarity and control here a universal best practice.

Open ground is also where deception works best. Decoys, false signals, and baited paths can pull an enemy out of position. In cyber, honeypots and canary tokens do the same: they invite movement into visibility and turn curiosity into evidence.

Real-world case: In 2021, the Microsoft Exchange Server vulnerabilities (ProxyLogon) exposed thousands of organizations’ email systems to the internet. Attackers rapidly exploited unpatched, public-facing assets—demonstrating why CIS Controls and NIST CSF stress the importance of inventory and minimizing the external attack surface.

Open ground isn’t “unsafe.” It’s honest. It shows you what you built.

Narrow Ground – Chokepoints, bridges, legacy stacks

Narrow ground is where everything funnels.

In military history, chokepoints decide battles because geometry becomes force. A smaller army can hold a larger one, not by being stronger, but by limiting the enemy’s options. Just think of the legendary last stand of Leonidas and the Battle of Thermopylae.

In cyber and cloud, narrow ground is often the infrastructure everyone relies on and no one wants to touch: legacy integrations, VPN tunnels, identity gateways, brittle on-prem choke points, systems tied to modern workflows by thread and habit. They become bridges. Bridges become targets.

If you harden one thing this quarter, harden your chokepoints, segment around them. Add compensating controls. Increase logging where applicable. Treat narrow terrain as sacred because when it fails, everything behind it is exposed. The MITRE ATT&CK framework’s focus on lateral movement and privilege escalation highlights why chokepoints must be secured and closely monitored.

Mini-case: The 2021 Colonial Pipeline ransomware attack targeted a single VPN account—an overlooked chokepoint with no multi-factor authentication. This breach underscores the criticality of securing and monitoring privileged access pathways.

Martial principles show up cleanly here. Wing Chun teaches that in close range, cutting angles and superior structure become everything. Trapping is about denying your opponent options. Narrow terrain does the same: it constrains movement and penalizes sloppy positioning.

Steep Ground – Visibility and defensibility, limited mobility

Steep ground is an advantage you must maintain.

High ground offers visibility and defensive leverage, but you don’t sprint on it. Movement becomes deliberate. Once you lose it, regaining it costs more than taking it did.

In cyber/cloud terms, the “steep ground” is where you place your crown jewels: production enclaves, privileged access vaults, critical logging pipelines, backup infrastructure, and identity governance, zones with strict access controls, immutable logs, and minimal pathways. NIST Special Publication 800-53 and CIS Controls both emphasize layered defenses and strong separation for critical assets, reinforcing the need for deliberate, hardened environments.

These environments should feel “steep” to anyone moving through them, including your own staff. That friction is the point. Steep terrain ensures enforcement of control.

Industry example: Major cloud providers routinely isolate customer data and management functions in highly restricted “steep ground” zones, applying controls from NIST SP 800-53 and CIS to prevent lateral movement and ensure containment if a breach occurs.

In Jiu Jitsu, this is akin to mount or back control: you don’t rush to snatch up a submission. You stabilize, isolate, and apply pressure through position and then finish. The defender who gets impatient on steep ground usually falls off it.

Encircled Ground – When you risk being surrounded

Encircled terrain is where isolation becomes lethal.

In war, encirclement breaks supply lines, erodes morale, and forces rash decisions. In cyber, encirclement often begins as “convenience” and ends as captivity: vendor dependencies, brittle third-party integrations, shadow IT no one owns, “critical” workflows held together by one person’s tribal knowledge.

The danger is that encirclement rarely feels dramatic at first. It feels normal until you need to restore. Until a vendor is down. Until the contract becomes leverage. Until the only admin is on PTO and the incident is already in motion.

Encircled ground demands exits: recovery paths, out-of-band access, air-gapped backups, and playbooks that restore connectivity without improvisation. CIS Control 11 and the NIST CSF Recovery Function both emphasize the importance of tested backup and recovery plans, as reliance on a single vendor or system is a strategic vulnerability.

Recent headline: In the wake of the 2022 Okta breach, organizations that relied exclusively on one identity provider faced business continuity risks. Those with tested out-of-band recovery and contractual exit clauses, as recommended by CIS and NIST, were able to restore operations more quickly.

If you don’t have those, you don’t have resilience. You have hope.

Expansive Ground – Flat, wide, tempting for overreach

Expansive terrain invites ambition. It also hides risk.

Movement feels easy because there’s “room,” but oversight drops as the supply lines lengthen. This is how empires, and cloud estates, collapse: not from one failure, but from accumulated, ungoverned territory.

In cyber, expansive ground is sprawl: dozens of cloud accounts, multiple providers, endless permissions, duplicated tools, integrations stacked on integrations. Sprawl isn’t evil. It’s simply unmanaged terrain.

Expansive ground demands scalable governance: infrastructure-as-code policies, automated compliance, continuous asset inventory, and hard limits on “just one more integration.” Otherwise, you end up “owning” too many things to defend any of them properly. Both NIST CSF and the CIS Controls call for continuous asset management and automated enforcement to keep sprawl in check.

This is where adversaries thrive, inside your noise.

Example: Several high-profile breaches, including Capital One (2019), were linked to sprawling cloud environments where asset management and policy enforcement lagged behind rapid deployment. This highlights why NIST CSF and CIS Controls call for continuous inventory and automated governance.

Choosing the Ground – Offense Through Selection

A leader’s first tactical choice is where to fight. Good generals choose terrain that favors their force and punishes the enemy’s approach. That’s a decision, not a reflex.

In cybersecurity, this is how you win before the breach: place valuable services behind hardened, observable layers and force attackers into monitored choke points. Make lateral movement steep. Make privilege escalation loud. Make time and friction the price of progress.

In cloud architecture, it refers to trust zones and least-privilege boundaries that govern movement, much as terrain shapes an army’s movement. If an adversary wants access, they must climb and be exposed while doing it.

In foreign policy, it means choosing diplomatic and economic levers rather than landing zones that stretch logistics and public support. Sometimes the “terrain” is public will. Sometimes it’s alliance cohesion. Sometimes it’s your economy. Burn those, and you’ve lost the campaign even if you win the first clash.

Choosing ground is an active defense. It doesn’t surrender initiative; it shapes the enemy’s options.

This is where martial deception becomes a strategy. A feint isn’t a lie, it’s an invitation. In Wing Chun, you draw the reach, trap the limb, clear the line, and strike at the same time. In Muay Thai, you show the jab to invite a teep to sweep the leg. In Jiu Jitsu, you offer the submission attempt you’re prepared to counter. Terrain selection works the same way: you present what looks like access, but what you built is a corridor of control.

Leadership, Discipline, and Knowing Your Soldiers

Sun Tzu insists a general must know his troops. That’s leadership in a sentence.

A leader’s indecision, ego, or poor communication is as lethal as bad geography. Poor leaders over-commit, under-communicate, or ignore warnings. They treat friction as disobedience and clarity as optional. That is how organizations drift into the “slovenly haphazard” disorder Sun Tzu warns about: plenty of tools, no coherence.

Discipline matters. Soldiers and engineers, treated with respect but held to standards, perform under pressure. Leniency breeds sloppiness; cruelty breeds silence. Both are operational risks.

Know your teams: strengths, fatigue thresholds, and tempo. Rotate duty. Limit emergency hours. Maintain training. In cloud and cyber, this includes on-call limits, respect for sleep, post-incident retrospectives, and psychological safety to report near-misses before they become incidents.

Morale shows up earlier than metrics. Leaders build the culture that sustains long campaigns.

Calculation Before Battle – The Work of Winning

Sun Tzu elevates calculation above impulse: the commander who measures many variables before engagement usually wins; the one who does not, loses.

This calculation is methodical: map terrain, count supplies (capacity), estimate enemy options, and plan contingencies.

In cyber, that means knowing your attack surface, understanding threat actor patterns, identifying likely pivot points, and building tested response runbooks. Rehearse, not because you expect a breach, but because you refuse to improvise under duress.

In the cloud, this entails calculating blast radius, recovery objectives, and the cost of complexity relative to the cost of resilience. It also means choosing fewer tools and mastering them, because every new platform is a new terrain you must defend.

In policy, it means calculating costs in treasure, trust, and time. Private-sector analogs are attention, capital, and brand.

Winning is the product of preparation. You cannot improvise a viable posture in a crisis.

Specific Strategies by Terrain – Practical Moves

- Open ground: prioritize speed and detection; keep public assets to a minimum; deploy decoys and canaries; monitor aggressively. (CIS Controls 1, 7; NIST CSF Identify & Protect).

- Narrow ground: enforce access controls and logging; funnel traffic through audited gateways; validate identity aggressively. (MITRE ATT&CK, NIST CSF Detect)

- Steep ground: design immutable environments and strict separation; place critical controls in high-ground enclaves with minimal human pathways. (NIST SP 800-53, CIS Control 13)

- Encircled ground: ensure out-of-band recovery, air-gapped backups, manual admin paths; maintain contractual exit clauses with vendors. (NIST CSF Recovery, CIS Control 11)

- Expansive ground: prune and consolidate; adopt infrastructure-as-code policies and automated compliance; set hard limits on new integrations. (CIS Control 1, NIST CSF Asset Management)

Every choice reduces the opponent’s options and preserves the defender’s leverage. In practice, aligning terrain strategies with proven frameworks isn’t bureaucracy; it’s how you translate doctrine into daily operations.

Parallels: Rome, Corporations, and Nations

Rome didn’t fail because it was weak; it failed because it could no longer pay for its expansion. The pattern repeats: a leader mistakes reach for control, stretches supply lines, and forgets the home base.

In business, over-expansion without integration kills cash flow and culture. In policy, interventions without sustainable objectives are hollow support. In cyber, growth without governance turns territory into liability.

The remedy is the same: select advantageous ground, keep logistics tight, and honor the limits of what you can sustain.

Closing: Ground, People, Calculation

Terrain teaches humility. It forces honesty about supply lines, political will, and human limits. Leaders must select ground that fits their forces, know their people well enough to deploy them without breaking them, and calculate relentlessly before contact. The best strategy isn’t the loudest; it’s the one most rigorously mapped to the ground and standards that define your domain.

Sun Tzu’s point is blunt: the general who prepares wins because he has already made many small victories before the first clash. The rest simply discover, too late, what the ground beneath them already knew.

The Next Step: Situations Reveal the Ground

Sun Tzu ends this chapter the way a good fighter ends an exchange: not with noise, but with control.

Terrain is not merely where you fight; it is what the fight allows. It determines which tactics are available, which movements are costly, and which victories are possible without incurring blood, bandwidth, or morale costs. The wise commander doesn’t “try harder” on bad ground. He changes the angle, changes the conditions, and shapes the enemy’s options.

Muay Thai does it with ring craft: take space, cut off exits, force exchanges where your strikes land cleanly. Jiu Jitsu does it with: position, then control, then submission, and sometimes with a ruthless setup: allowing the opponent to chase the submission you expected, only to counter when they overextend.

Terrain works the same way. Choose it well, and you’re not only defending but shaping the enemy’s approach until their “attack” becomes the opening you built the environment to reveal.

That leads us directly back to the principles that opened this chapter:

“The natural formation of the country is the soldier’s best ally; make use of it to your advantage.” Because once you understand the ground, you stop fighting the fight the enemy wants, and start forcing the battle they cannot win.

And when leadership is weak, orders are unclear, and duties are unfixed, the result is exactly what Sun Tzu promised: utter disorganization, not because the enemy was brilliant, but because the ground exposed what was already unstable.

The highest standard remains unchanged: the general who advances without vanity and retreats without fear, whose only thought is to protect his people and do good service, is the jewel of the kingdom.

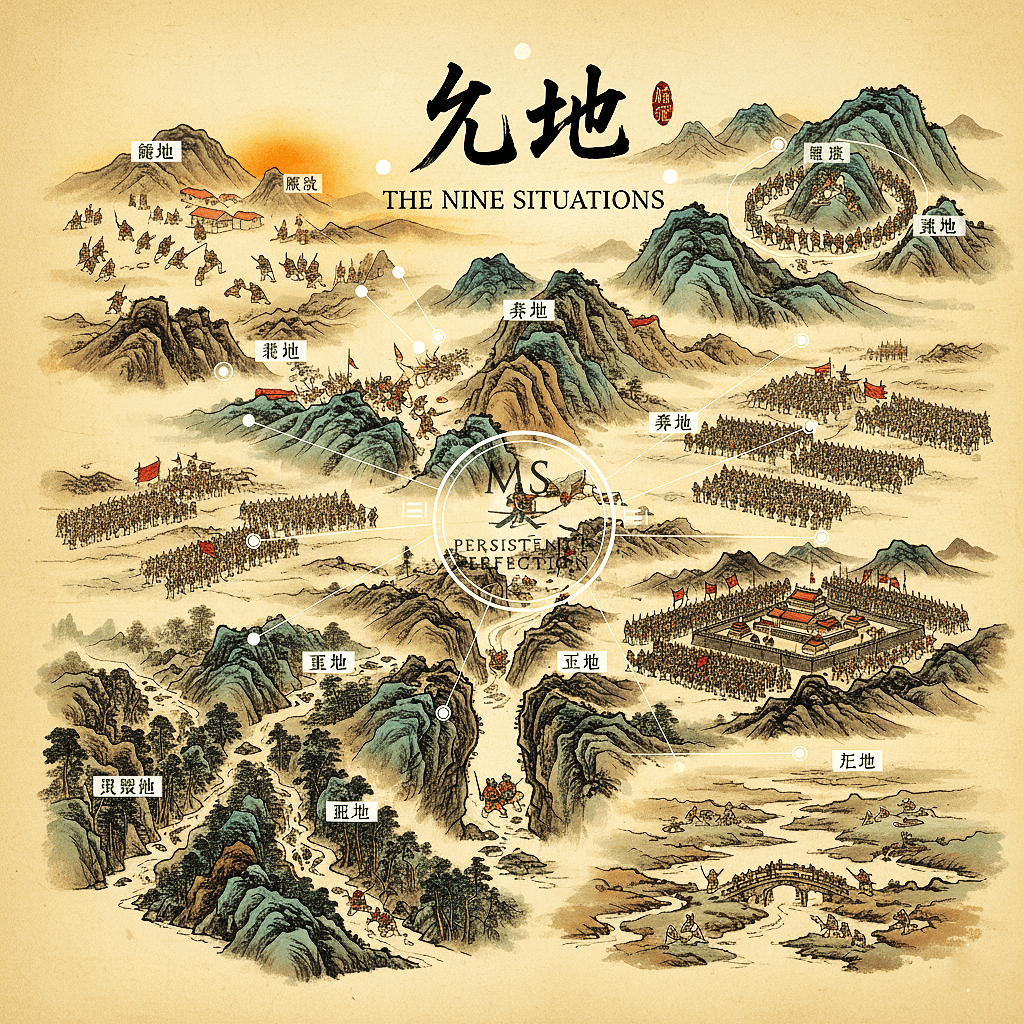

Bridge to Part XI – The Nine Situations

Terrain teaches you what is possible. The Nine Situations teaches you what to do when possibility collapses into reality, when you’re advancing, retreating, encircled, trapped, deep in enemy ground, or approaching decisive contact.

It is a doctrine of movement under pressure: acting in accordance with circumstances without losing coherence.

You’ve learned how to read the ground.

Next, you’ll learn how to fight on it.