The principles: Begin by seizing something which your opponent holds dear; then he will be amenable to your will.

…Concentrate your energy and hoard your strength.

The principle on which to manage an army is to set up one standard of courage which all must reach.

Whoever is first in the field and awaits the coming of the enemy will be fresh for the fight. – Sun Tzu

Context and Purpose

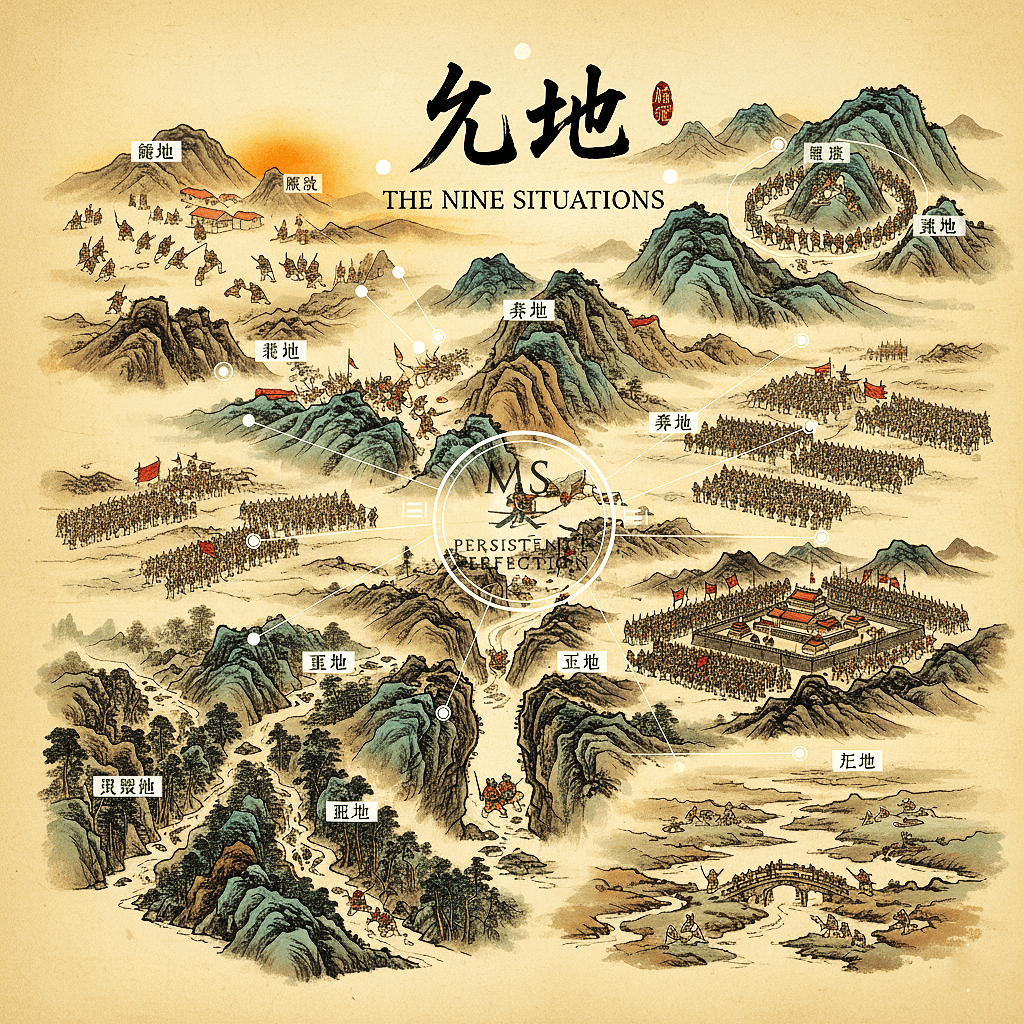

Sun Tzu’s Nine Situations maps the kinds of ground and circumstance a commander can face – from favorable positions to trap-laden ground. Each situation demands a different posture: sometimes you press; sometimes you withdraw; sometimes you wait. The lesson is tactical discrimination: don’t treat every fight the same.

In the modern world, those “situations” are organizational states: besieged systems, fleeting windows of access, deep entrenchment, overextended operations. Knowing which box you’re in changes everything you do next.

Leadership and Morale: The Human Center

Before tactics, a note about people. Sun Tzu insists that a general must know his soldiers. That’s not a platitude; it’s an operational fact.

- Morale is intelligence: exhausted teams miss indicators, fail to follow playbooks, and make desperate mistakes.

- Leadership is maintenance: rotating shifts, realistic on-call expectations, paid recovery time after incidents, and clear chains of command preserve discipline.

- Respect plus standards: treat your people with dignity and hold them to standards. Leniency breeds sloppiness; cruelty breeds silence. Both are fatal.

A leader who ignores morale loses the fight long before the enemy arrives. That’s as true for an infantry company as for an incident response roster.

Deception and Perception Management

Sun Tzu: All war is based on deception. In practice, that means shaping what the opponent and the population believe.

- Information operations: propaganda, curated narratives, and coordinated messaging have always been instruments of power. Orwell’s line, “We have always been at war with Eastasia,” is a cautionary parable about manufactured consensus.

- Modern analogue: in cyber, deception shows up as honeypots, false telemetry, and misinformation campaigns; in statecraft, as narratives that create vulnerability or strength where none objectively exists.

- Ethical frame: defenders use deception for detection and deception to raise the cost for attackers (e.g., canary tokens). Democracies must guard against the weaponization of truth at home; businesses must avoid misleading stakeholders.

Deception works because humans fill gaps with a story. Control the story; you alter the field.

Fight Only When Necessary

Sun Tzu and Mr. Lee agree: war is terrible; fight sparingly. The principle is simple: act only when the expected gain exceeds the cost.

- Cost-calculation is non-negotiable: time, attention, capital, reputational risk.

- In cyber: a public takedown, a disclosure, or active defense escalation must be measured against downtime, legal exposure, and adversary escalation risk.

- In policy: interventions must have clear exit conditions and sustained domestic support. If you cannot sustain it, don’t start it.

Discipline supersedes impulse.

“If the Enemy Leaves a Door Open, Rush In” to Follow the Energy

Sun Tzu’s pragmatic injunction to exploit openings is simple: when an opponent’s guard falls, capitalize immediately. In fighting, it’s like watching for your opponent to drop their hands or go for a spinning attack; in security, it’s a window of opportunity for decisive action.

- Cyber example (defense): detect a lateral movement attempt and immediately isolate the segment, block the credential, and pivot forensic capture. The quicker the isolation, the smaller the blast radius.

- Cyber example (offense/emulation): when a red-team discovers a misconfiguration, follow the chain-of-trust to map further exposures before the window closes.

- Business/policy: when a competitor shows strategic weakness (supply disruption, PR crisis), acting quickly with a measured offer can consolidate position. But always have your logistics in place; quick gains that can’t be held are hollow.

Following the energy multiplies the effect, but only if you’ve done the work beforehand to sustain the ground you’ve gained.

The Nine Situations, Condensed & Modernized:

- Dispersive ground – you’re among your people; maintain cohesion.

Cyber: internal incidents; prioritize comms and transparent leadership. (e.g., during the 2021 Log4Shell crisis, organizations that communicated quickly and openly with their teams contained risk more effectively.) - Facile ground – easy ground, many exits; avoid traps of complacency.

Cyber: dev/test environments misused as production; lock and audit. - Contentious ground – disputed control.

Cyber: contested supply chains; prioritize integrity of build pipelines. - Open ground – mobility advantage.

Cyber: cloud-native agility, move quickly, but instrument heavily. (Example: When a vulnerability like Heartbleed emerges, organizations that can rapidly update and redeploy cloud resources while monitoring all endpoints gain a decisive edge.) - Intersecting ground – convergence of routes/partners.

Cyber: shared services; segregate trust boundaries and enforce SLAs. - Serious ground – stakes are high; commit only with full readiness.

Cyber: critical infrastructure; assume regulation and public scrutiny. - Difficult ground – constrained movement.

Cyber: legacy stacks; carve compensating controls and minimize exposure. - Hemmed-in ground (trapped) – the enemy can encircle.

Cyber: breached islands due to vendor lock-in; prepare out-of-band recovery. (e.g., during the NotPetya outbreak, companies with alternate vendors or recovery paths minimized downtime, while others suffered prolonged outages.) - Desperate ground – fight with everything; no other option.

Cyber: blind-fire incident with full emergency playbook; declare crisis, invoke war-room, use all hands.

Each situation requires a plan in advance, not improvisation in the heat of chaos. For those new to Sun Tzu: dispersive ground means your own territory, open ground is the public cloud, and hemmed-in ground is where your options are tightly constrained.

Prescriptive Playbooks (Operational Guide)

Below are short playbooks, or practical checklists, you can paste into an incident binder.

A. Besieged System (Hemmed-in/Trapped Ground)

- Isolate affected segments (network ACLs, VLANs).

- Enable out-of-band admin (jump boxes, console access).

- Invoke containment RTO/RPO playbook.

- Engage legal & communications.

- Stand up a dedicated recovery team; rotate shifts.

- After action: root cause, patch, and inventory third parties.

B. Fleeting Access (Open/Facile Ground)

- Capture forensic snapshot immediately (memory, session tokens).

- Harvest IOC, block indicators at perimeter.

- Perform rapid threat hunting to see lateral movements.

- Patch/vault credentials, revoke tokens.

- Debrief and harden the vector.

C. Retreat & Reconstitute (Dispersive/Retreat Scenario)

- Execute planned fallback to secondary infrastructure.

- Verify backups and boot from immutable images.

- Communicate to stakeholders with controlled cadence.

- Rebuild in clean environment; stage verification before full restore.

D. Stronghold Defense (Steep/High Ground/Serious Ground)

- Minimize human access; require jump hosts & MFA.

- Immutable logging to secure audit trails.

- Periodic red-team tests; continuous monitoring.

- Harden supply lines: vendor SLAs, redundancy, and a tested DR plan.

E. Rapid Exploitation (If a Door Opens)

- Pre-authorize small rapid-response teams for exploitation windows.

- Legal/ethics checklist signed off on in advance.

- Capture intelligence, seal pivot paths, and convert to defense artifacts (detections, blocks).

Each playbook starts with people: assign roles, cap on-duty hours, and rehearse quarterly.

Final Thought: Calculation, Culture, and the Necessity of Restraint

Sun Tzu’s closing insistence, calculate before battle, remains the core discipline. The leader who wins has already counted costs, supply, morale, and terrain. The one who loses discovers those facts mid-fight.

That brings us back to the principles that opened this chapter:

- Seize what the opponent holds dear: not for theater, but to create leverage and force predictable reactions.

- Concentrate energy and hoard strength: preserve focus, avoid waste, and don’t spend force just to feel decisive.

- Set one standard of courage: culture must hold under pressure, or your best playbooks become paper.

- Be first in the field and wait: preparedness buys calm, and calm buys time – it’s the rarest advantage in crisis.

In cyber and statecraft, the rule remains unchanged: prepare, preserve people, exploit opportunities, deceive judiciously, and fight only when victory is likely and sustainable. As Robert E. Lee warned, “It is well that war is so terrible, otherwise we should grow too fond of it.” So only fight when you have no other option. When you do fight, move decisively, use the force necessary to end the threat, and leave no doubt in your opponent’s mind so they will never make that mistake again.