The principle: “There are not more than five musical notes, yet the combinations of these five give rise to more melodies than can ever be heard.” — Sun Tzu

Adaptation Over Assumption

In Maneuvering, we learned the art of movement and how to turn posture into progress. Now Sun Tzu takes the next step: variation.

Variation is the discipline of adaptation. Not improvisation for its own sake. It’s controlled flexibility and fluidity; the kind that keeps a force alive while in motion.

Sun Tzu’s warning is ruthless: Predictability is the slow death of strategy. Every organization that wins too long risks repeating itself.

Every CISO, every architect, every nation-state faces the same danger: When your patterns stabilize, your adversary’s job gets easier.

Attackers study rhythm.

They hunt repetition.

They exploit formula.

What you repeat becomes your weakness.

Static Defenses, Dynamic Threats

In cybersecurity, repetition feels like discipline:

- the same checklists

- the same daily, weekly or quarterly assessments

- the same scanning cadence

- the same unchanged playbooks

It feels stable but it’s stagnation dressed as process.

Meanwhile attackers evolve hourly.

Their payloads morph.

Their lures update.

Their timing adapts to human fatigue cycles.

They don’t overpower blue teamers; they systematically outlearn them.

Sun Tzu’s guidance, “alter your plans according to circumstances,” isn’t merely poetic.

It’s operational doctrine. Security isn’t a system. Security is a cycle.

- Every breach teaches.

- Every false alarm reveals.

- Every routine day hides patterns waiting to be broken.

The teams that adapt fastest aren’t the biggest.

They’re the most fluid and adaptable.

Variation is awareness in motion.

Red Teams, Blue Teams, and the Dance of Adaptation

Variation is the heartbeat of adversarial testing. Red teams live in uncertainty: improvisation, deception, broken rhythm. Blue teams train in structure: detection, containment, resilience.

A mature organization doesn’t let them exist as siloed tribes. It merges them into purple teaming, where the creativity of offense and the rigor of defense evolve together.

- Red exposes blind spots.

- Blue turns discovery into discipline.

- Together they adapt.

This is the martial logic of sparring:

- Wing Chun’s angle changes, where the same attack comes from different entries vs simply straight lines.

- Muay Thai’s broken rhythm, where timing destroys expectation.

- BJJ’s transition → position → submission sequence, where variation becomes game, set, match.

Each engagement becomes rehearsal for reality. You’re not preparing for yesterday’s threat. You’re learning from tomorrow’s rehearsal. That’s Sun Tzu’s Variation: adaptation as preparation.

Cloud Security: Adaptation as Architecture

Cloud environments shift constantly:

- APIs update

- services deprecate

- compliance rules revise

- identity models evolve

- integrations multiply

Static thinking is fatal in a fluid system. Cloud security is variation embodied.

Infrastructure-as-code lets architecture evolve at speed. Automation turns intent into consistent action, but without visibility, variation becomes drift.

Sun Tzu’s metaphor of water fits perfectly: Water adapts to its container yet always seeks its level.

Cloud engineers do the same:

- change with the environment, without losing alignment

- allow flexibility, without losing control

- evolve configurations, without losing accountability

Adaptation is necessary. Principles are non-negotiable.

Foreign Policy and the Trap of Predictability

Nations decay when their doctrine ossifies.

The American foreign policy establishment has often fallen into this trap over and over again:

- Cold War containment repeated even after the context changed.

- counterinsurgency tactics applied to environments that defied them

- interventions driven by reflex rather than awareness

Vietnam: A doctrine built for conventional warfare in Europe applied to guerrilla conflict in jungle terrain. The U.S. measured success through body counts and attrition, while the enemy measured it through will and time. Same playbook, wrong war. Predictable escalation met adaptive resistance.

Afghanistan: Twenty years of rotating commanders, each bringing their own tactical variation, but all operating under the same strategic assumption—that nation-building through military presence could succeed where it had failed for empires before. The tactics changed every 18 months with each new general. The doctrine never did. The enemy simply waited.

Iraq 2003: Intelligence assumptions treated as certainties. A swift conventional victory followed by the assumption that democratic institutions could be installed through force. When insurgency emerged, the U.S. applied a counterinsurgency doctrine designed for different conflicts. By the time adaptation occurred (the Surge), years of predictable responses had already created the conditions for ISIS.

But perhaps the most revealing pattern is the rhetorical one: every emerging threat becomes “the new Hitler,” every conflict the next World War II.

- Saddam Hussein was Hitler.

- Gaddafi was Hitler.

- Milosevic was Hitler.

- Assad was Hitler.

The framing never changes. The enemy is always being Chamberlain in 1939 and being “appeasers of Hitler.” The infantile argument is always to stave off the newest existential threat to humanity. This isn’t strategy, it’s intellectual predictability masquerading as moral rectitude and always sticking by the banal cliche “never again,” whether is really applies or not.

World War II was a unique conflict: a mechanized, industrial-scale war between nation-states with clear battle lines, total mobilization, and, foolishly, unconditional surrender as the objective. Applying that framework to insurgencies, civil wars, and regional conflicts doesn’t just fail tactically, it reveals a dangerous inability to see the situation as it actually is.

The Hitler analogy serves a purpose: it short-circuits debate, frames inaction as appeasement, and makes intervention seem inevitable. But it’s also the ultimate form of strategic predictability. When every threat is Hitler, every response becomes World War II, and variation dies.

Variation in statecraft means reading each situation fresh, not recycling last decade’s doctrine into a new century, and certainly not recycling a doctrine from 80 years ago. In each case, tactical adjustments happened but strategic doctrine remained rigid. That’s the opposite of Sun Tzu’s teaching: vary tactics, never principles. These conflicts varied neither.

The Global War on Terror: The Ultimate Failure of Variation

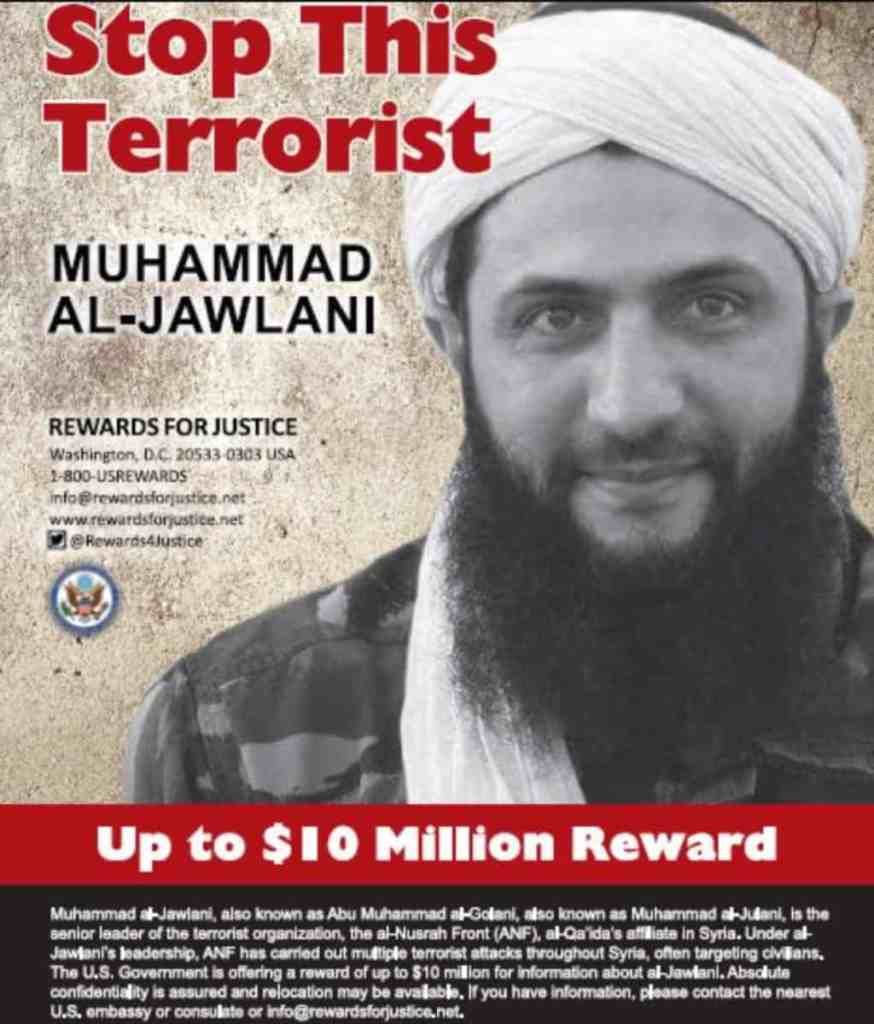

And then there’s the final, most damning example of strategic predictability: Ahmed al-Sharaa, originally known as Abu Mohammed al-Jolani, who once led al-Qaeda’s Al-Nusra Front or Jabhat al-Nusra in Syria and spent years detained by U.S. forces as a terrorist in Iraq, was welcomed to the White House in November 2025 by President Trump.

He once had a $10 million U.S. bounty on his head. He founded al-Nusra Front, al-Qaeda’s Syrian branch. Now he’s a partner in the Global War on Terror.

This isn’t adaptation. This is strategic incoherence dressed as pragmatism.

Twenty-four years after 9/11, after trillions spent, after Afghanistan and Iraq, after “we don’t negotiate with terrorists” became doctrine, the United States now supports the former head of the very organization we invaded multiple countries to destroy.

The justification? He helps combat ISIS. The same ISIS that emerged from the predictable chaos of the Iraq War. The same conflict where al-Sharaa himself fought as a leading al-Qaeda member against U.S. forces.

This is what happens when doctrine ossifies while reality shifts. When every threat is framed through the same lens (“the new Hitler”), when every intervention follows the same playbook, when strategic thinking atrophies into bureaucratic reflex you end up shaking hands with yesterday’s enemy because you can’t recognize that your framework has failed.

Sun Tzu’s warning rings clear: predictability invites exploitation. The GWOT’s predictable responses—invasion, occupation, counterinsurgency, withdrawal created a cycle that adversaries learned to exploit.

They adapted. We repeated.

And now, the former al-Qaeda commander who once fought U.S. forces receives a hero’s welcome at the seat of American power. Not because the threat changed. Because we ran out of variations on the same failed strategy.

Predictability in diplomacy invites miscalculation.

Predictability in force posture invites escalation.

Predictability in cyber deterrence invites probing.

Again, as an example, at the extreme end of predictability lies Pearl Harbor.

Japan didn’t strike out of pure ambition; it struck because the U.S. cut off:

- 90% of its oil

- vital steel

- food

- rubber

- machinery

- industrial materials

A nation deprived of resources enters what Sun Tzu called death ground, the place where maneuver becomes inevitable.

- Predictable embargo.

- Predictable deterioration.

- Predictable desperation.

- Predictable strike.

Sun Tzu understood the principle: the more rigid your doctrine, the more your opponent will shift. Nations, like networks, must evolve, or decay through repetition.

Variation Without Confusion

Adaptability is not inconsistent. Sun Tzu warned that blind variation, change for its own sake,

creates disorder.

The rule is simple: Vary your tactics. Never vary your principles.

In cybersecurity, the principles are visibility, trust, and accountability.

In cloud architecture, they are governance and clarity.

In foreign policy, they are restraint and realism.

Change how you respond.

Never change why you respond.

That’s how variation becomes strength rather than noise.

Modern Lessons in Motion

Across every domain, the real art lies in learning faster than you decay:

- In cybersecurity, adapt playbooks to every alert, not just every quarter.

- In cloud: treat configuration as a living organism, not a static diagram.

- In diplomacy: update doctrine before circumstances force your hand.

Predictability invites attack.

Curiosity creates resilience.

Sun Tzu didn’t worship flexibility. He prized awareness in motion, responsiveness guided by principle.

That is how you survive modern complexity: move → learn → realign → repeat.

That’s variation.

From Variation to Awareness

Variation teaches movement. The next lesson teaches perception.

In Chapter IX, The Army on the March, Sun Tzu turns to the signals that guide a force in motion, how to read the terrain, sense morale, detect fatigue, and recognize when momentum turns into danger.

If Variation in Tactics is about adapting to survive, The Army on the March is about understanding the signs that tell you whether your adaptation is working.

Bringing us full circle to our opening principle: “There are not more than five musical notes, yet the combinations of these five give rise to more melodies than can ever be heard.”

In our next installment, we’ll discuss perception and reality in networks, in nations, in martial skill, and most critically, in ourselves.